I’ve been home for two weeks now, and I struggled throughout those two weeks to think of an appropriate farewell entry for betsyinjamaica.blogspot.com. I have finally realized that any farewell entry must convey a sense of thankfulness, and that is what I have set out to do.

I’ve been home for two weeks now, and I struggled throughout those two weeks to think of an appropriate farewell entry for betsyinjamaica.blogspot.com. I have finally realized that any farewell entry must convey a sense of thankfulness, and that is what I have set out to do.My return to the States was equal to any made-for-tv movie—my parents greeted my long-haired, khaki-clad, hippie self at the airport with hugs, a cooler filled with my favorite American treats, and a dozen pink roses. (Thanks, Mom and Dad!) The following days were a whirlwind of joyful reunions and how-was-its. I am more than grateful for the welcomes that my friends, family, and church community have extended.

However, I simply can’t erase from my mind the months of joy, sorrow, and discovery that my Jamaican friends, Jamaican family, and Jamaican church community extended to me during the past year. Everywhere I turn is Jamaica—from the necklaces I wear to my morning coffee to my missionary clothing tan lines. I am irrevocably tied to the concepts of poverty, justice, simplicity, and solidarity—as returned volunteers are wont to say, “I’m ruined for life.”

I spent my last week in Jamaica dissolving in tears whenever I tried to say goodbye. In between packing and orienting the newbies (who are fabulous and were fabulously patient with my rollercoasters of emotion), I had little time to say goodbye, and most of the time I did have was spent sobbing on Miss Doris’ shoulder. It didn’t feel right—these people didn’t ask for me to drop into their lives and play with their children. They didn’t ask for me to become their friend, but somehow, I did. And then I up and left them.

It is here in this entry that I can effectively list my gratefulness to the people of Mount Friendship: thank you for guiding me into the work I was sent to do. Thank you for letting me witness true compassion and devotion. Thank you for letting me hold your babies and for making me feel included in village politics and gossip. Thank you for your smiles and for your simplicity. Most importantly, thank you for forgiving me during those times in which I’m sure I let you down.

It is here that I can thank my friends, family, and church community for their support during the year: thank you for caring. Thank you for your cards and notes and packages and magazines. Thank you for the expensive phone calls and expensive plane tickets. Thank you for trying to wrap your head around the ideas of poverty and justice. But most importantly, thank you for letting Miss Doris, Mr. Brooks, and a village called Mount Friendship into your consciousnesses and into your hearts. Be assured that I am happy to be home with you all.

It is here that I can thank the Passionist Volunteers International staff and extended network for their training, patience, and development. Thank you for challenging me. Thank you for feeding me and listening to me whine. Thank you for talking about service and solidarity and the poor. Thank you for being available and for being a surrogate family. I couldn’t have done this without you.

Jamaica and Passionist Volunteers International will always be a part of who I am…those two entities have shaped me, for better or for worse.

I ache for it all--I miss the sunsets. I miss my roommates. I miss my dog. I miss my oranges. I miss the sweetly lilting rhythms of Jamaican Patois. I miss Doris and Brooks. I miss the earnest choruses before Sunday service. I miss the feel of Kadean’s little hand in mine. Unbelievably, I miss the god-awful smells of downtown Kingston and the hideous braying of goats in the bush.

I wish the best to Matt, Jared, Sarah, Charity, and Tracy, “newbies” no longer. They are well-equipped to handled the challenges that Jamaica will undoubtedly hurl at them this year. I envy them: they have it all before them.

But I now have the chance to join the ranks of PVI alumni—I’m eager to join the recruiting process and can’t wait to visit next year’s orientation. I’m currently working on what I refer to as my “big-girl life”—the next phase. I have the extraordinary opportunity to start another kind of service. Come fall, I will be a teacher in a Catholic high school and can continue the journey of justice. As much as I miss my Jamaican way of life, I understand that the next stage of my life will be no less exciting or fulfilling.

So, thanks. Thanks Jamaica, thanks Rhode Island, thanks PVI. Thanks for making me into who I am today, in this moment. I love you all.

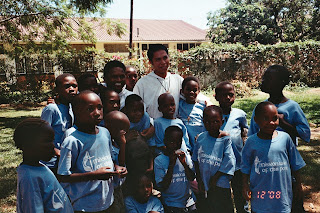

But there were lots of hugs, lots of giggles with my favorite kids, lots of really beautiful moments. In fact, I’m not even going to pretend that I have the literary capabilities to describe some of the encounters I have had over these past few days. Let’s leave it at this: the time I spent hosting a camp in my home community was precious and has given me memories that I will treasure forever.

But there were lots of hugs, lots of giggles with my favorite kids, lots of really beautiful moments. In fact, I’m not even going to pretend that I have the literary capabilities to describe some of the encounters I have had over these past few days. Let’s leave it at this: the time I spent hosting a camp in my home community was precious and has given me memories that I will treasure forever. I don’t want to mislead you all. I am eager to get home—I can’t wait to see the family that has supported and loved me during this zany year. I’m aching to see my friends and the thought of a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee-and-bagel combo makes me giddy. Don’t get me wrong, people. I’m quite ready to trade in my view of Kingston harbor with the skyline of Providence.

I don’t want to mislead you all. I am eager to get home—I can’t wait to see the family that has supported and loved me during this zany year. I’m aching to see my friends and the thought of a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee-and-bagel combo makes me giddy. Don’t get me wrong, people. I’m quite ready to trade in my view of Kingston harbor with the skyline of Providence.

At the present moment, we’re almost halfway through our camps. We’ve spent time in Devon Pen and Tom’s River, and Mount Friendship and King Weston await us in coming weeks. As I type this very entry, my hands are stained with the green dye from today’s camp in Tom’s River, and our car is packed with tomorrow’s rice, snacks, and equipment for relay races and jump roping contests.

At the present moment, we’re almost halfway through our camps. We’ve spent time in Devon Pen and Tom’s River, and Mount Friendship and King Weston await us in coming weeks. As I type this very entry, my hands are stained with the green dye from today’s camp in Tom’s River, and our car is packed with tomorrow’s rice, snacks, and equipment for relay races and jump roping contests.

I’m putting out my own Just So You Know right now…Just so you know, June 13th is my father's birthday! I may not be home to help him blow out all er…36…candles, but know that I’ll be doing it in spirit.

I’m putting out my own Just So You Know right now…Just so you know, June 13th is my father's birthday! I may not be home to help him blow out all er…36…candles, but know that I’ll be doing it in spirit.

But I can’t carry the metaphorical big green stick forever—it is not my job to police recycling. If this is a project that will last, then I need to step back and let it last. And when I removed myself, I saw a few things that made that old green heart of mine swell with pride.

But I can’t carry the metaphorical big green stick forever—it is not my job to police recycling. If this is a project that will last, then I need to step back and let it last. And when I removed myself, I saw a few things that made that old green heart of mine swell with pride.

This is an experiment. As volunteers, our hopes are modest: we know we work in areas that are destitute. The people with whom we work are not particularly concerned about saving the Earth—their worries focus on feeding their children and keeping a roof over their heads. But we hope that this project will give them dignity—a chance to escape the toxins of the plastics and a place to put their garbage. Volunteer work is all about sustainability: Can your project survive? How will it last if you abandon it? We are not yet sure that this project is sustainable. We are giving it until Earth Day: April 22. It is then that the schools will tell us if this is something they want to continue on their own terms.

This is an experiment. As volunteers, our hopes are modest: we know we work in areas that are destitute. The people with whom we work are not particularly concerned about saving the Earth—their worries focus on feeding their children and keeping a roof over their heads. But we hope that this project will give them dignity—a chance to escape the toxins of the plastics and a place to put their garbage. Volunteer work is all about sustainability: Can your project survive? How will it last if you abandon it? We are not yet sure that this project is sustainable. We are giving it until Earth Day: April 22. It is then that the schools will tell us if this is something they want to continue on their own terms. The children played freely with the supplies. An intense soccer match soon developed. Little girls took the buckets I had brought and went fishing in the river. One of the mothers appeared with sugar and more water and managed to stretch the juice for everyone. Another mother organized an efficient line at snack time and handed out the biscuits before I knew what was happening. The teenagers who had appeared created a schedule of races and jumping rope contests.

The children played freely with the supplies. An intense soccer match soon developed. Little girls took the buckets I had brought and went fishing in the river. One of the mothers appeared with sugar and more water and managed to stretch the juice for everyone. Another mother organized an efficient line at snack time and handed out the biscuits before I knew what was happening. The teenagers who had appeared created a schedule of races and jumping rope contests. I plan. It’s what I do. I am learning, however, that even the most meticulous of plans do not always work in the wild bush of Jamaica. Children can be rough and supplies can run out. A small, one-day camp for children turns into a community event—but that is okay—it is wonderful. At times, the event was chaotic, but it was beautiful chaos. Here, it truly does take a village to raise a child—and a volunteer.

I plan. It’s what I do. I am learning, however, that even the most meticulous of plans do not always work in the wild bush of Jamaica. Children can be rough and supplies can run out. A small, one-day camp for children turns into a community event—but that is okay—it is wonderful. At times, the event was chaotic, but it was beautiful chaos. Here, it truly does take a village to raise a child—and a volunteer.